Thoughts on Integrating Data and Design - Text Analysis

Following a project utilising various forms of text analysis including supervised and unsupervised methods. We take a look at how these might be applied in human centred design projects. Including classification, entity recognition, natural language processing and clustering

- Author

- Joshua McCarthy

- Published

- Mon, Jun 15 2020

- Last Updated

- Mon, Jun 15 2020

This article is aimed at data scientists and analysts with some experience in text analysis and potentially some exposure to design thinking. If you have no exposure to text analysis, this blog provides a brief, easy to interpret overview of some potential outcomes, though it is worth keeping in mind that the source is a company providing text analytics as a service.

Human Centred Design

Human Centred Design is a framework moving into the spotlight established by the democratisation and widespread implementation of Design thinking (Liedtka, 2018). Where Design Thinking exists as a framework enabling “non-designers” to understand and utilise many of the tools and processes deployed in the practice of design. Human Centred Design seeks to refine existing, and develop new, tools and methodologies which increase focus on the people directly or indirectly interacting with design processes and outcomes. These two methodologies are closely interlinked, IDEO the leading organisation in Human Centred Design has described Design Thinking as;

“Design thinking is a human-centered approach to innovation that draws from the designer’s toolkit to integrate the needs of people, the possibilities of technology, and the requirements for business success.”

- Tim Brown, Executive Chair of IDEO (IDEO Design Thinking, n.d.)

Human Centred Design tools are often those democratised through Design Thinking, ideally increasing the human focus of projects influenced by Design Thinking and other similar frameworks alongside Human Centred Design. The following video provides a brief overview of the Human Centred Design process, this blog focuses on the first “Inspiration” phase identified in the video.

What is Human-centered Design? from IDEO.org on Vimeo.

Building Understanding and Unstructured Data

At the core of Human Centred Design is building understanding and empathy, for users and people who have been, or may be impacted by the focus of the project. Conventionally, this could be a product, service, or system, more recently growing in application to strategies, policies and all areas of business, impact and government models. Projects often dedicate a large portion of resources to this front-end phase, in some cases this exploration and sharing of understanding comprises the whole project. Broadly, this phase consists of deploying specialised ethnographic research to immerse in, observe, and record the context that the project exists in, the personalities, motivations, and external influences of the individuals therein, placing particular focus on capturing the needs and wants of these individuals. The process attempts to distil understanding of the context into information which evokes empathy informing idea development and decision making to be more appropriate to the people and context.

As with most qualitative research methods building understanding and empathy in Human Centred Design is synonymous with unstructured data. The challenge of distilling and synthesising this information is an intensely human process, requiring many hours of skilled team members, users and context experts collaborating to draw the most relevant and meaningful insights forward from the experience gained. A process which could benefit from the considered and informed application of Text Analysis and Natural Language Processing, as have the related fields of qualitative research and ethnography (Arnold & Fuller, 2019; Cheah et al., 2018).

Particularly relevant challenges of the inspiration phase described by IDEO are;

Initial secondary research to become “fluent” in culture and context of the subject group to foster beneficial communication, carefully weighed against developing preconceptions and bias, this challenge is ongoing as new discoveries and deeper understanding often require additional supplementary research.

Synthesis and distillation of the outputs from contextual research and observation, particularly in understanding the narrative and vernacular of stakeholders involved. Consisting of, interview transcripts and interviewer notes, observation notes, workshop transcripts and workshop outputs; ideas in the form of sketches, notes, layouts and processes, practitioner notes attempting to record; underlying motivations, emotions, goals, and influences.

Understanding people and creating opportunities for more inclusive and personalised experiences through their direct contributions such as long form feedback, prior communication, user journals, cultural probes, and profiles. This process balances deep understanding of individuals and grouping with others. Grouping through similar mindsets, personalities, mental models, and connections in; motivations, challenges and needs rather than demographics or circumstances.

Becoming Fluent

Preliminary secondary research is often one of the first steps to internalising the information required to effectively communicate in a new environment (Design Kit, n.d.; #TiSDD Method, n.d.). Human Centred Design follows similar methodologies to those observed in other disciplines, though often with greater focus on discovery and insight than rigour. As research progresses and the collected corpus grows it becomes increasingly challenging to find additional valuable and reliable information, additionally, an individual’s working memory limits their ability to draw parallels and similarities between parts of the corpus. Text analysis provides an opportunity to address these problems.

As the corpus grows so does the ability of a model to understand what is meaningful and the theme of the corpus. At a certain threshold, depending on the focus of the corpus, there is sufficient information to develop a model to classify the relevance of new articles. Providing a library of unchecked documents and utilising the model to perform initial identification of potentially valuable documents or to crawl through prior research corpora for useful documents may speed up information finding after collection of easy to identify articles. This method presents the risk of creating tunnel vision in the corpus, limiting the breadth of knowledge observed, conversely if the initial corpus is too varied, the model will be unlikely to produce valuable output. Use with these considerations in mind continue to present an unexplored path forward to expanding the available knowledge base.

Particularly relevant to longer duration projects, a large body of knowledge collected over a long period presents a challenge to practitioners and the limits of human memory. Being able to draw out valuable insights across research requires identification of commonality and an understanding of the relationship between the research collected. Here text analysis could highlight, particularly in documents collected separately in time or project lifecycle, commonality, recurring themes, and entities. Highlighting ongoing important terms in the vernacular of the community and opportunities to review previously understood information with new understanding.

Synthesis and Distillation

Human Centred Design is overflowing with tools and frameworks for drawing insights from ethnographic research (Design Kit, n.d.; Stickdorn & Schneider, 2011). In my experience these tools rely on a human parsing and internalising the information before sensemaking can occur. Particularly when working across a large team of design researchers, potentially in collaboration with professional ethnographers, anthropologists and other experts, the volume of unstructured data can be overwhelming, leading to important details not translating across groups. Stakeholder maps and empathy maps are familiar tools to Human Centred Designers and people exposed to Design thinking, these tools also present opportunities for integration with text analysis.

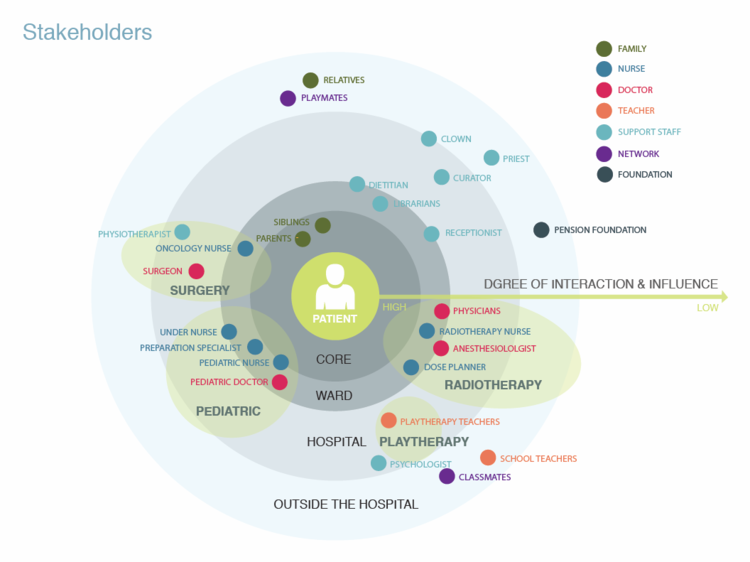

Stakeholder map from Tara Mullaney project Dumbo

Stakeholder maps are an ideal candidate for entity recognition, particularly across a corpus of contextual interview transcripts. A stakeholder map places the focus or most impacted individual in the centre, generally the user, then identifies the stakeholders that relate to that user, layered by the amount of impact of influence between themselves and the central person. Collecting multiple interviews across similar users, enables entity recognition across the transcripts. This process could draw out recurring stakeholders augmenting the human identification processes, further, entity recognition could aid in layering stakeholders by providing addition evidence of their prevalence across the corpus. Augmentation being key to this integration, the level of impact and emotional responses between two entities is not always observable from interview transcripts. Similarly, contextual research aims to identify influences not identified by the subjects themselves, conducting interviews in the subject’s context, allows observation about the direct and indirect interactions between stakeholders.

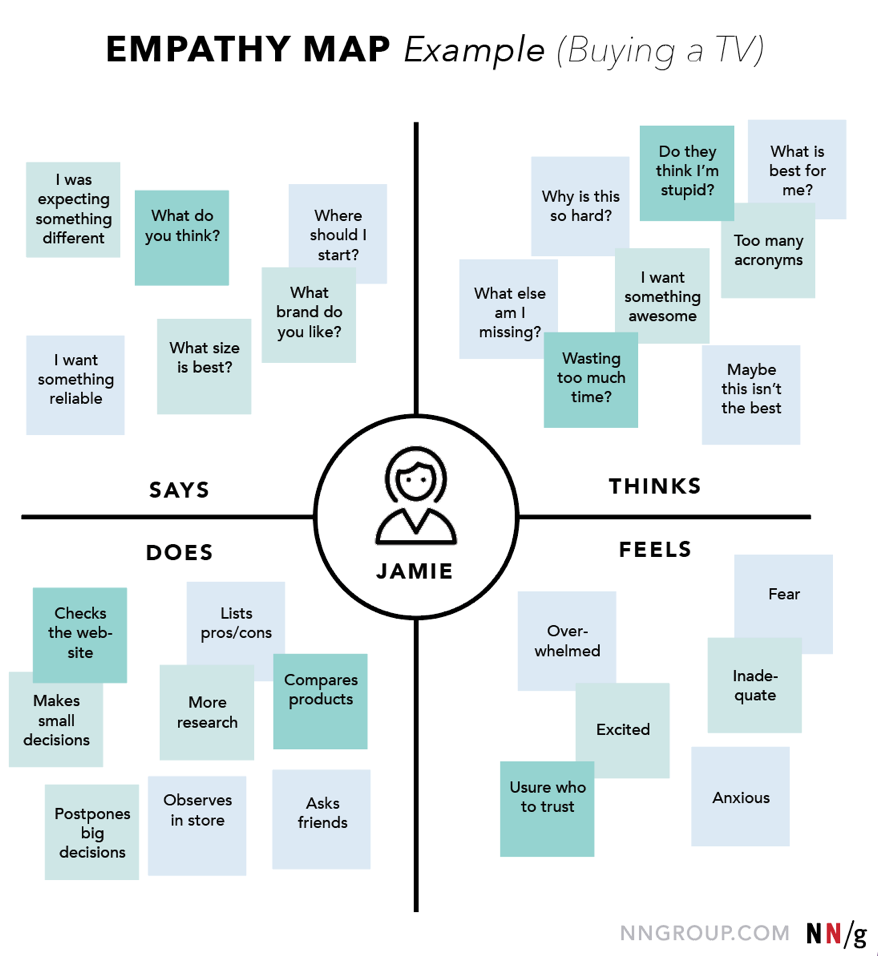

Empathy Map from Neilsen Norman Group

Empathy maps are another tool to structure the synthesis of research outputs. The map attempts to communicate the broader range of influences, their outcomes, conflicts and inconsistencies as a user or stakeholder has an experience. Development of these maps requires review of all the material collected about the user or user groups and the experience and the distillation into key themes, ideas, quotes and important observations falling into the categories of says, thinks, does and feels, often templates provide the supplementary step of identify the pains and gains of the user’s experience. Here, text analysis of grouped and selected documents such as interview transcripts or user journals can extract, recurring themes, topics, key words, and phrases within groups. These or similar artefacts are often included in empathy maps providing an additional method to draw these insights forward or inspire the practitioner toward new thoughts and understanding. The somewhat experimental fields of sentiment analysis and emotional recognition within natural language processing could prove particularly useful in identifying underlying information, however, particularly if transcripts are not taken verbatim, these methods may identify information about the recorder rather than the subject. Ensuring that the human interaction outside of the spoken and written words is still accounted for in the mapping process, in combination with the analytic outcomes, requires special consideration as this represents a core value of Human Centred Design.

Understanding People

Collecting this depth of information about users and people involved in the project builds the deep understanding and empathy expected of a Human Centred Design project. An outcome of this process is the ability to identify similarities between individuals and group individuals based on a variety of observations, avoiding the use of conventional demographics and focusing on motivations, needs and challenges (P, 2020). Further refinement into persona occurs, where each persona represents a collection of these observations to communicate and build empathy (Experience, n.d.) for the values they represent. A shortfall of personas is the tendency to average out individuality, create ideals and unrealistic representations. Recent developments integrating inclusivity and accessibility into design have highlighted the need to treat each person as an individual with specific similarities to other individuals, rather than broad grouping. This approach is similar to the methods deployed in text analysis particularly in matrix decomposition. This presents an opportunity to overcome a limitation inherent in human created persona, the need to reduce to the number, variety, and subtlety of differentiation in order to be useful for human use, often resulting in oversimplification of a complex relationship. Practitioners could scale the detail and differentiation within groups dynamically, based on similarity identified by modelling, potentially creating separate groupings for each target observation, and not exposing the observed understanding to the bias of demographics. Enabling more robust persona and the ability to provide a more inclusive experience to individual users, this process must be monitored for other bias inherent in the deployment of machine learning particularly for under-represented populations.

Final Thoughts

This blog post seeks to identify some specific use cases for Text Analysis in the practice of Human Centred Design particularly in the early stages of a project, discussing the impact, benefit, and potential limitations of integrating the two disciplines. Each use case presents an opportunity to augment existing approaches, while there is an opportunity to develop radically new methodologies, starting with integration into existing practice enables both sides to better understand the benefits and limitations of each approach, and provides a clearer path to implementation a first step in any change process (Kotter & Cohen, 2002). The application of data science and specifically text analysis could reduce the amount of human effort required to complete each piece of the framework identified, shortening timelines, and reducing cost while maintaining value. Even if text analysis outcomes consist mostly of low hanging fruit, there is still opportunity for the unexpected, and integration frees up capacity for the practitioners to look for deeper meaning. Finally, something to be covered in a later blog post is the potential application of text analysis to identify similarity between past, present and future projects through comparison of relationships between users, people, outputs, and research.

References

Arnold, T., & Fuller, H. J. A. (2019). In Search of the User’s Language: Natural Language Processing, Computational Ethnography, and Error-Tolerant Interface Design. In T. Z. Ahram & C. Falcão (Eds.), Advances in Usability, User Experience and Assistive Technology (pp. 36–43). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94947-5_4

Cheah, Y.-W., Paine, D., Ghoshal, D., & Ramakrishnan, L. (2018). Bringing Data Science to Qualitative Analysis. 2018 IEEE 14th International Conference on E-Science (e-Science), 325–326. https://doi.org/10.1109/eScience.2018.00076

Design Kit. (n.d.). Retrieved 11 June 2020, from https://www.designkit.org/methods/21

Experience, W. L. in R.-B. U. (n.d.). Just-Right Personas: How to Choose the Scope of Your Personas. Nielsen Norman Group. Retrieved 12 June 2020, from https://www.nngroup.com/articles/persona-scope/

IDEO Design Thinking. (n.d.). IDEO | Design Thinking. Retrieved 11 June 2020, from https://designthinking.ideo.com/

Kotter, J. P., & Cohen, D. S. (2002). The heart of change: Real-life stories of how people change their organizations. Harvard Business School Press.

Liedtka, J. (2018, September 1). Why Design Thinking Works. Harvard Business Review, September–October 2018. https://hbr.org/2018/09/why-design-thinking-works

P, M. (2020, April 9). Kill Your Personas. Medium. https://medium.com/microsoft-design/kill-your-personas-1c332d4908cc

Stickdorn, M., & Schneider, J. (2011). THIS IS SERVICE DESIGN THINKING: Basics, Tools, Cases. WILEY.

#TiSDD Method: Preparatory research. (n.d.). Retrieved 11 June 2020, from https://www.thisisservicedesigndoing.com/methods/preparatory-research